Dr. Marc Salzman’s patients rarely complain about post-surgical pain. That’s because he’s an expert at using ultrasound guided nerve blocks to mitigate pain. A double-board certified plastic surgeon, award-winning educator, and Clarius user, Dr. Salzman recently shared his expertise in a one-hour webinar.

You can watch a recording of the full webinar to see all of the three plastic surgery cases he presents. Or read a synopsis of how he uses handheld ultrasound to perform accurate TAP (transversus abdomininis plane) blocks and LAP (lateral approach pectoralis) blocks to help his patients recover faster, with minimum pain.

A Plastic Surgeon’s Approach to a Safe Pectoralis Block

“My method to perform a LAP block is much different from an anesthesiologist. I prefer to approach the block from the side of the table instead of doing it above the clavicle and going over the second rib. For one thing, I don’t want to stand beside the anesthesiologist and the tubes they are monitoring. And second, I want to avoid the risk of getting near the lung. I prefer to be parallel to the chest wall, which is preferable for plastic surgeons. Since we don’t have an x-ray in my operating room to monitor for a pneumothorax, I feel this is a safer approach. We also cover more area with this approach.

An ultrasound-guided block of the medial and lateral pectoral nerves can be used for both cosmetic and reconstructive submuscular placement of either tissue expanders or breast implants.

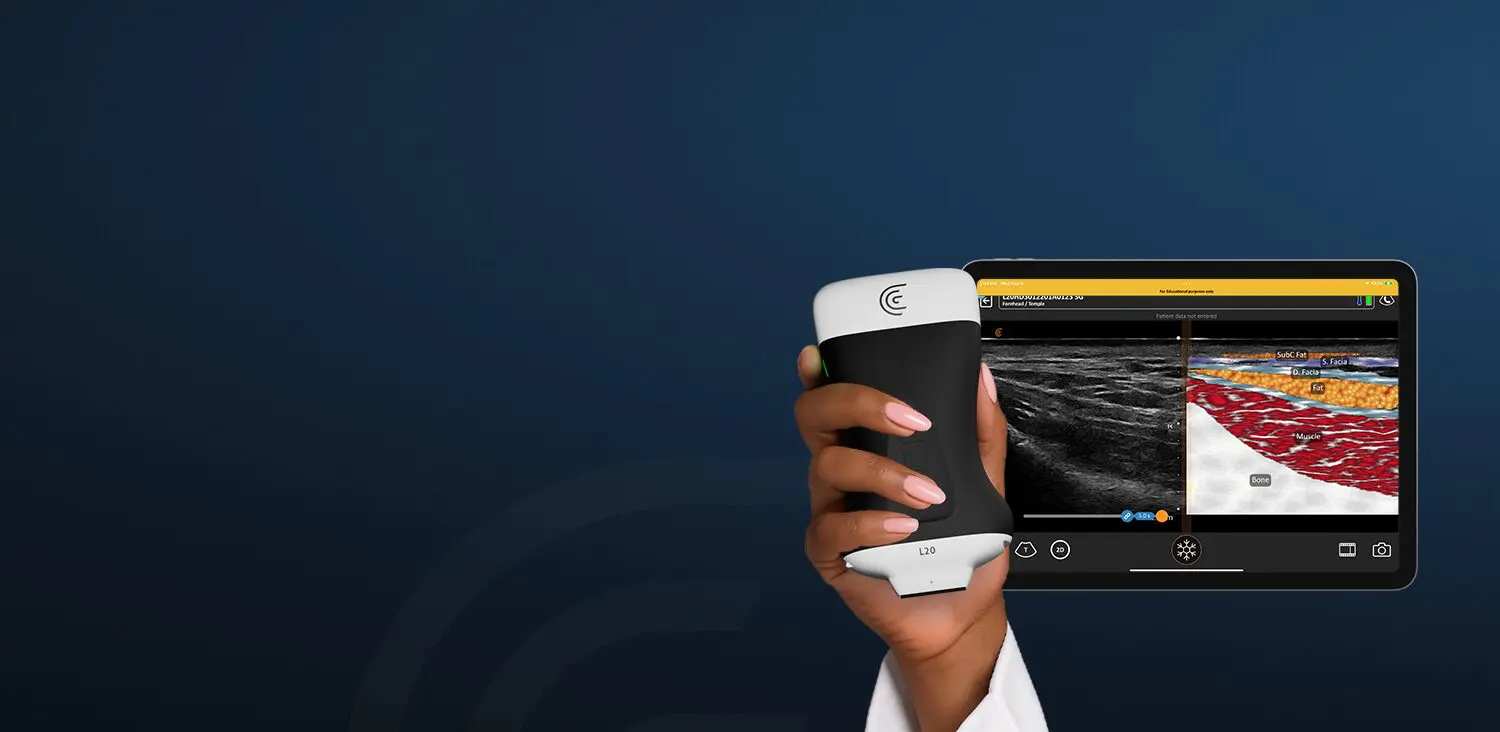

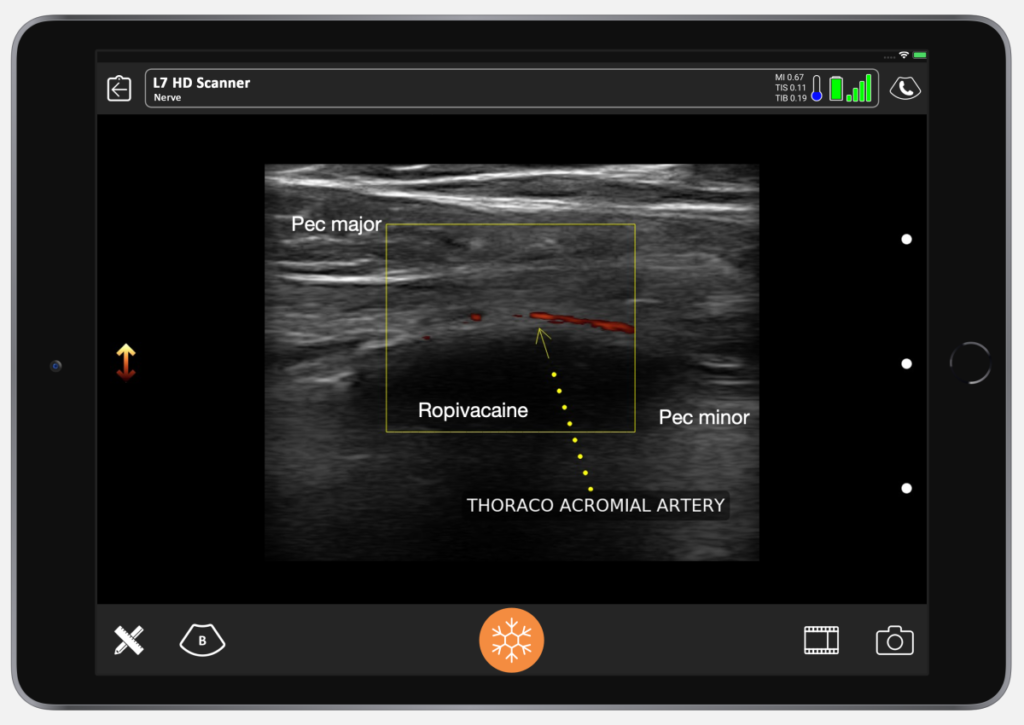

On the illustration above, you see the lateral pectoral nerve, which comes out medial on the chest wall. It comes from the lateral cord to the brachial plexus. You also see the medial pectoral nerve. The thoracoacromial artery comes off the axillary artery and runs with the lateral pectoral nerve. It’s important to block both nerves because they both have some sensor and mostly motor input to the pectoralis major.

The Preferred Medication

I perform this block immediately after the induction of anesthesia. The LMA may not be in yet, but the patient is asleep. We put a Tagaderm on the transducer surface with a little sterile jelly. I use 15 cc Ropivacaine per side to block the lateral and medial pectoral nerves. We don’t use the more expensive Exparel because it isn’t economical for a $7,000 operation to use medication that costs $350. Ropivacaine seems to last 8 to 10 hours, and it seems to work fine. That’s the L-isomer of Marcaine®.

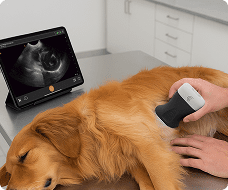

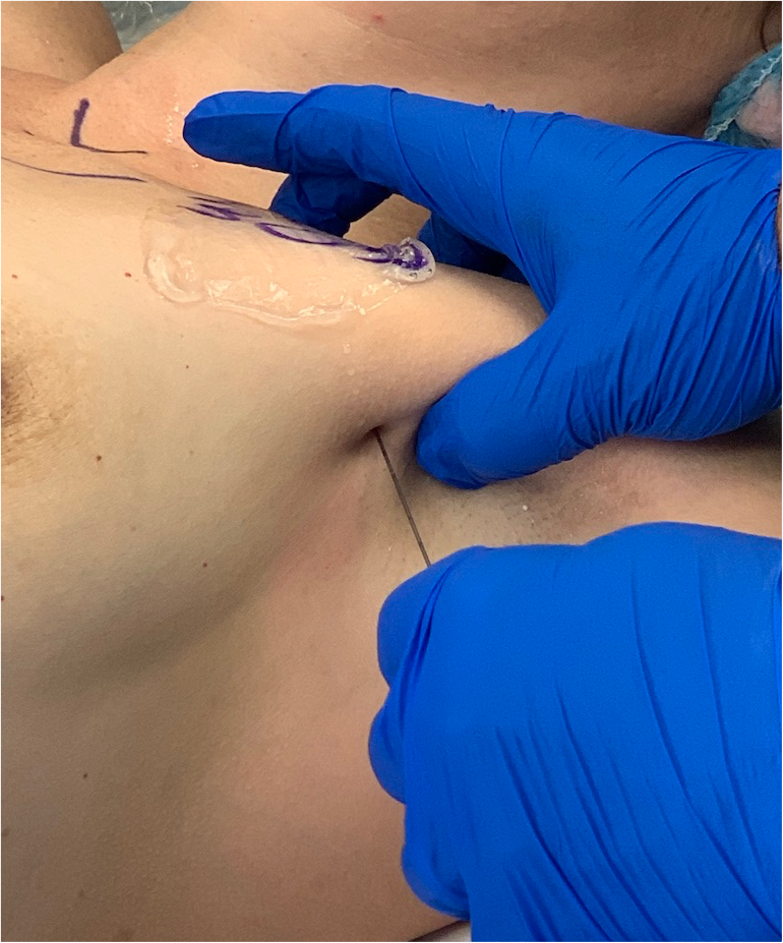

My set-up includes the Clarius L7 handheld ultrasound scanner, the local anesthetic, a SonoBlock needle by Braun and my iPad on a stand with a heavy bottom. We use the same iPad from the exam room in the operating room. You’ll notice there are no dangling wires on this ultrasound machine. I love it.

About the Needle

Depending on the brand of needle, they have little reflectors that are either diamond shaped or triangular. These allow visualization and angles up to 60 degrees. This is important as the needle comes out of being in-plane and is parallel to the long axis of the transducer, at this angle it can be harder to see the needle in the ultrasound image. You want to be as parallel possible, which is sometimes difficult with a heavier patient. This type of needle makes it a lot easier to see in tissue than, for example, a 22-gauge spinal needle.

On this normal chest wall anatomy, imaged above, you see the pec minor over the second rib. This is the pectoralis major plane. There’s the normal architecture of fat, skin, subcutaneous tissue and the support structures over the fat. It is between the pec minor and the pec major.

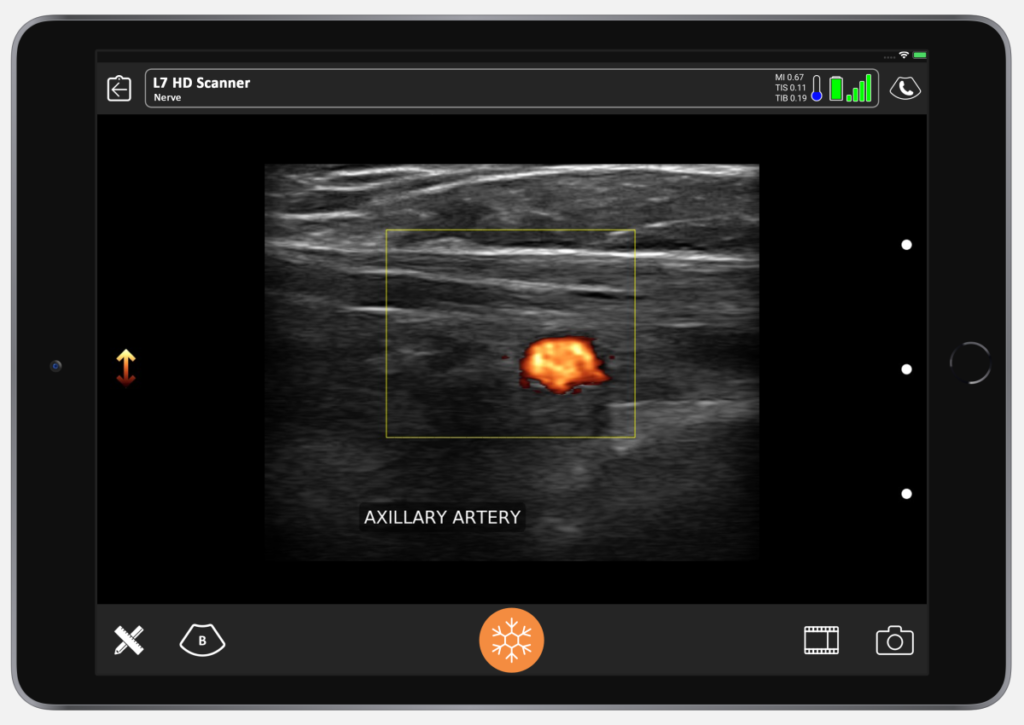

Our goal is to block from lateral to medial. First, I use the doppler setting to find the thoraco-acromial artery. I recommend going off the axillary and finding the thoraco-acromial because that’s the most medial aspect of your block. By going lateral to medial, you’re covering more surface area.

On the anatomy of a patient above, I’ve marked the location of the axillary artery that we found with ultrasound. The thoraco-acromial artery is coming off the axillary artery. As we know, the lateral pectoral nerve runs with the thoraco-acromial. Based on the location of the medial pectoral nerve, we want to put the bolus of our block right in the general red circle.

I took the picture above after the Ropivacaine was in. You can see the nerve is bathed in Ropivacaine. The thoraco-acromial artery is easy to find here with Doppler.

I start by placing my thumb in the anterior axillary line, just below the lateral border of the pectoralis major. And then, I line up the Clarius device so that it’s parallel to the long axis of the transducer, and I insert the needle.

Then, the nurse gives a small test dose of saline so we can see that we’re in the right place.

Once I confirm the anechoic spread between the pec major and the pec minor, the nurse switches to Ropivacaine. You can then see the muscle split. It’s so satisfying to see that. The muscle splits in the avascular plane between the pec major and pec minor. I don’t always go to find the thoraco-acromial. I know that if I go almost to the extent of the needle, I’m going to get to the distance I need. It’s usually nine centimeters from the lateral pec border to get to the lateral pectoral nerve.

What you see below the image of the needle is called reverberation artifact, which is normal when you look at metal under ultrasound.

The whole procedure takes 30 seconds per side. It’s really fast – a maximum of 2 minutes from start to finish.

What are the Advantages to Using a Nerve Block?

For years, I didn’t perform blocks. Now, I find that patients don’t suffer a pectoralis spasm because we’re paralyzing the muscles. We don’t see implants riding up the axilla anymore. We don’t use bands. No fancy bras. Nothing. With this block, the patients are in and out of the PACU between 15 and 20 minutes after they’re finished. There’s less narcotic and faster recovery.

I’ve done more than 500 of these blocks now, and we’ve had just one minor complication. We had one single AE because I believe some medication extravasated in a very thin patient into the brachial plexus. She had some deltoid weakness for about four or five hours and that was about it.

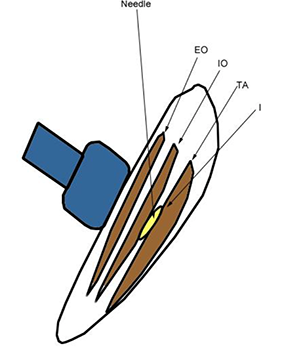

For a TAP (transversus abdominal plane) block, the anesthetic is placed between the internal abdominal oblique and the transversalis, which is where the yellow color is noted above.

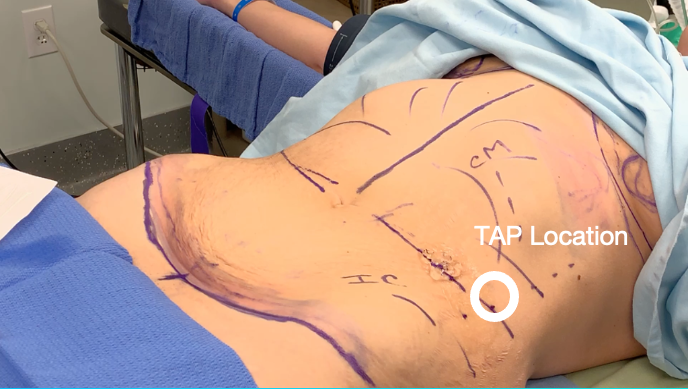

This image shows the TAP location. It’s described as “Petit’s triangle,” between the iliac crest and the costal margin along the anterior axillary line, just above the umbilicus.

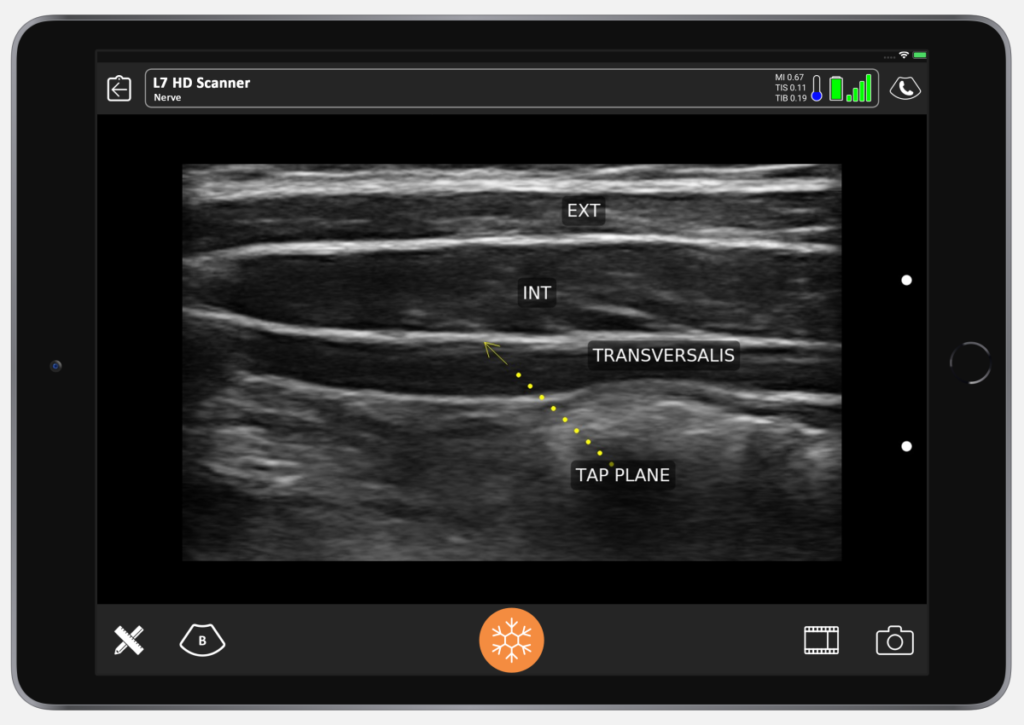

Above is what it looks like under ultrasound. You can see skin, the fascia, external abdominal oblique muscle, and fascia between the external and the internal. The biggest muscles are always the internal abdominal oblique. Then you have the transversalis, and if you look closely, you can usually see peristaltic activity in the peritoneum. This is our TAP plane, between the transversalis and the internal oblique.

We use the belly button as a marker, putting our needle in just above the anterior axillary line. In the ultrasound video below, the needle is sitting in the center of the transducer. The test dose goes in first.

You can see the needle entering the TAP plane. You can see the axis of the needle and the transversalis fascia being depressed. You’ll see the needle pop and then the fascia will pop back, that’s how you know you’re in. When the fascia pops back, you give your test dose.

Once you see the saline is in the right place, follow with Exparel. Here you’ll see the Exparel separating the internal from the external. You’ll see the same anechoic spread as we saw with the LAP block. It’s simple.

In summary, LAP and TAP blocks can add patient comfort. It makes for easier recovery for our patients following the placement of breast implants and abdominoplasty procedures. It has really revolutionized my practice.

It also sets me apart from my peers as being more cutting edge. Patients are happier with easier recovery. Without a block, people are walking around for a week in total spasm after surgery. Our patients are going to dinner. It’s a wonderful, wonderful block.”

Dr. Salzman has been practicing in Louisville, Kentucky since 1992. He also teaches his innovative techniques with online lectures and around the United States. Dr. Salzman also lectures plastic surgery residents at the University of Louisville.

An ultrasound user since 2012, Dr. Salzman switched from a laptop ultrasound to the Clarius L7 HD in 2019. Read his article about why ultrasound is essential for every plastic surgeon.

To learn more about how easy and affordable it is to add Clarius HD to your plastic or cosmetic surgery practice, contact us today or request an ultrasound demo to see the difference high definition imaging makes.