When Dr. Pete Tonseth was invited to go on a surgical mission to Biri Island in the Philippines, there was doubt about how much he could help. He was a radiologist, and in the years that the mission went to the island, there was no medical imaging equipment available. The initial reaction from the team was, “What use is he going to be?”

I went initially as being whatever they needed me to be, which might have been cleaning the equipment or scrubbing the floors or holding a retractor,” he says. But he brought a Clarius scanner, and it was clear from the first day that a radiologist that could use ultrasound made a big difference to the mission.

Dr. Pete Tonseth, a radiologist and nuclear medicine physician, travelled as part of International Surgical Missions (ISM) in a group of 35 volunteers comprised of surgeons, anesthetists, nurses, and support crew.

Over the years, the ISM team had brought equipment on the mission and left them on the island. But they didn’t have medical imaging—there weren’t any X-ray, CT, or ultrasound machines. Transporting large pieces of equipment had to go by road and ferry, and the island was a couple of days away from Manila. There was no surgical care on the island, and care at many of the hospitals in Northern Samar was privatized and inaccessible to the people who couldn’t afford it.

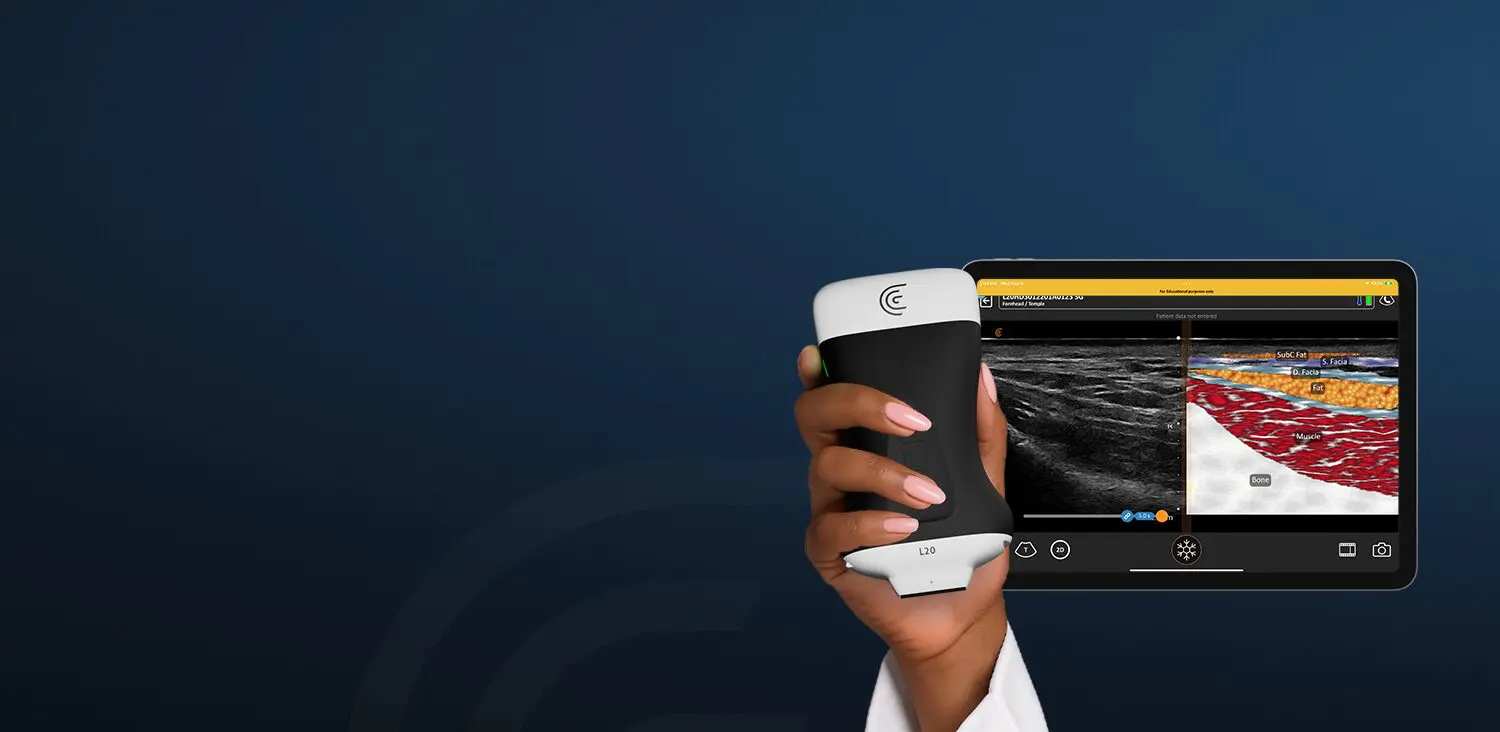

It didn’t take long to show the surgeons and anesthetists how to use the scanner. Dr. Tonseth recounts how he put the scanner, battery, his phone, and the instructions on the table, and said, “Make it work.”

It took about six minutes for someone who had never touched an ultrasound device before to create an image. While interpreting an image is a different matter, the ease of capturing a high-quality image sets the foundation for ultrasound to become more widely used. “As a point-of-care ultrasound device, image quality is important because you are making decisions on a limited study,” he says.

The mission team started with triaging patients from four sites across Northern Samar and evaluating who would be most suitable for the types of surgery they were able to do. There was a range of conditions, from inguinal hernias to large ovarian masses to thyroid disease. During the mission, the team also looked at chronic conditions. Since the mission was only two weeks long, the team also looked at correcting chronic conditions to eliminate problems that could come up throughout the year when they wouldn’t be there, such as cholecystitis from cholelithiasis.

Dr. Tonseth shared a room with a pathologist. He set up the scanner, cooling fan, and battery charger on a small table right at the bedside. This proximity allowed them to work closely together: he would do a breast biopsy, hand the specimen to the pathologist for a diagnosis, and learn if the patient had a benign or malignant lesion. The patient would then go into their surgery knowing how serious their condition was.

The portability of ultrasound has made it almost an essential part of the surgical care,” he says. It was unexpected how much the surgical management changed from having an ultrasound device. Surgeons who had practiced at Biri Island before without medical imaging were now adapting their practice, asking him to scan patients and making decisions based on the imaging.

The value of ultrasound access was clear from the first day. One of Dr. Tonseth’s first patients was a young woman with spina bifida, and a suspected abscess. It was critical to differentiate the dural sac from the abscess. Imaging the patient allowed the surgeon to operate with confidence knowing that they weren’t working near dangerous structures.

In another case, the team treated a woman with a large pelvic mass. The surgeons were at first concerned about operating, since they were unsure of what they were dealing with. But with an ultrasound, they were able to see what was going on and accurately pinpoint the exact location of the mass, thus avoiding cutting into the solid portion of a large ovarian tumour.

Post-operatively, ultrasound was used for analgesia. Clarius allowed anesthetists to localize the needle placement for a transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block, and patients were able to leave the hospital without needing pain medication. It wasn’t something Dr. Tonseth considered possible—his expertise was in diagnostic imaging, and he didn’t foresee the potential for therapeutic uses.

Ultrasound proved itself to be essential at every stage—from the triage stage, to perioperatively, and then for post-op pain relief. In future missions, Dr. Tonseth plans to expand his role and bring a radiology resident and sonographer. And even outside of the field of diagnostic imaging, ultrasound changes things in the hands of general practitioners, nurses, internists, and so on. For the first time, patients could have their own medical records on their phones.

“It’s hard to express the impact that this had,” Dr. Tonseth says. Scanning the patient, working with the surgeon to see the details they need, doing the operation—“you have to be there.”