Dr. Christopher Elliott, a global equine sports medicine and rehabilitation expert, recently shared his experience with treating thoroughbred horses at his practice in Australia during a webinar. Following are excerpts that highlight his best practices for measuring and documenting pathology for accurate diagnosis and for measuring progress during rehabilitation.

“Following is an ultrasound exam video captured with my Clarius L7 Vet on a three-year old thoroughbred racehorse. Here we see a lesion with another edge lesion. We start at the top of our lesion and then we’re just moving nice and smooth down the leg, identifying where our lesion is, getting a gauge of what’s going on. This is my preliminary scan, I’m working out where everything is, going down to the bottom our lesion. Now we know what we’re dealing with, we’re going to go back and then we’re going to take our regular intervals, document our images, and then get our measurements.

In the following images, which were taken a little while ago at my equine practice, the patient details have been removed. I usually start at four centimeters to the distal accessory carpal bone, so DACB CM, centimeters and then eight. The reason I do it in that order is because then I can just click and delete the number and change it instead of deleting the whole thing and rewriting it all.

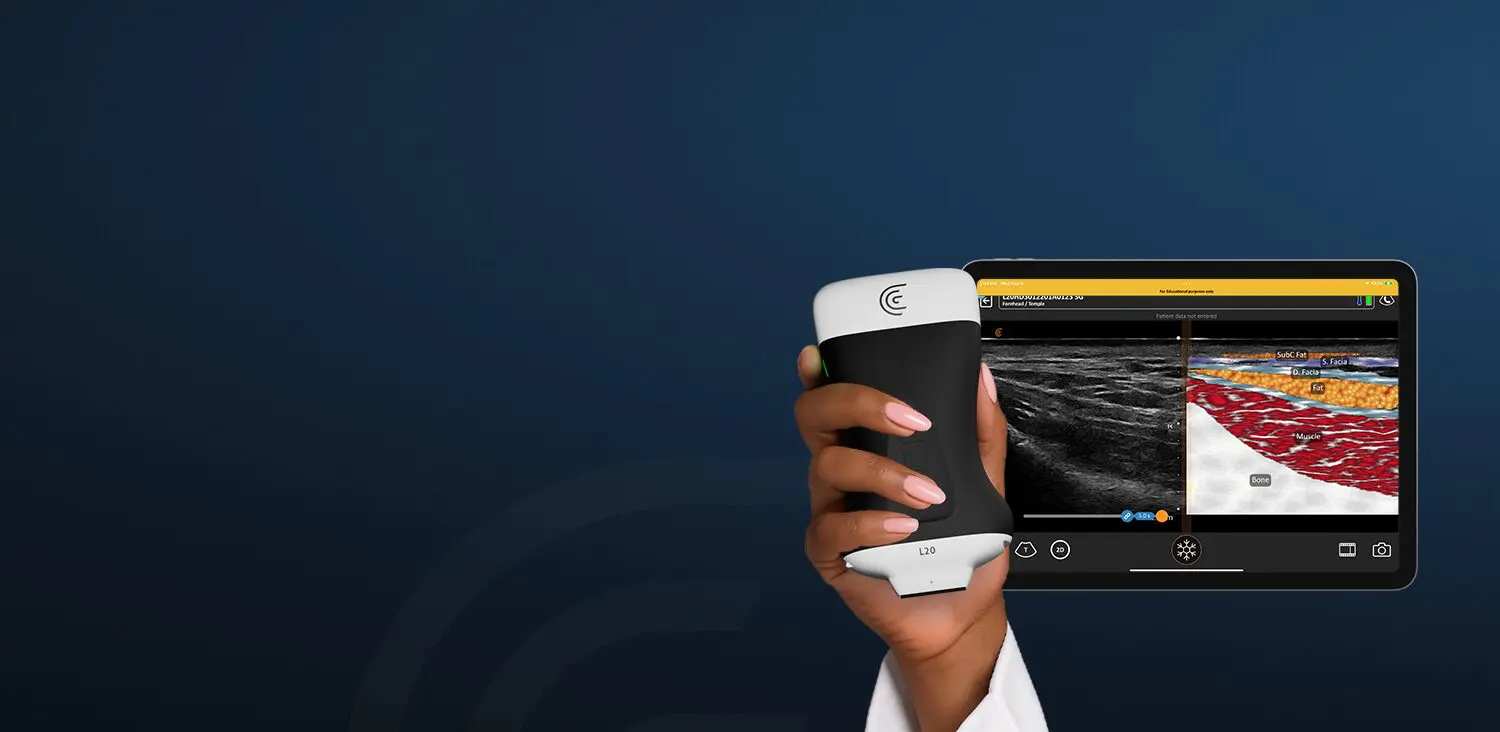

Above on the right, I’m measuring the cross-sectional area of the SDFT. On a thoroughbred racehorse, the cross-sectional area of an SDFT is going to be round in general, measuring about that 0.8 centimeters squared, or definitely less than one centimeter squared, depending on the size of horse. But usually, it’s around about 0.7, 0.8, 0.9. We can already start to see that this cross-sectional area is a bit big at 1.1.

Moving down the leg, we’ve gone from eight to 12 cm, and now we’re starting to see our lesion. I usually move down every four centimeters. I’m scanning through, but recording it every four centimeters. Once I start to find lesions, I’m recording every two centimeters to document it. We can see here above that we’re starting to see quite a significant enlargement of our cross-sectional area, 1.3, 1.4. And then, we’re starting to find a really definable lesion. And we’re using the second ability of the trace to actually work out how much of our cross-sectional area of this tendon is damaged.

At the 16-centimeter image above on the right, we’re looking at 1.58 centimeters squared, so that’s a big tendon that is significantly enlarged. The lesion we’re looking at is over six millimeters. If we’re looking at six on top of 158, it’s about 4% damage inside that lesion. It’s 50% larger than it should be, and the damage is about 5%. These types of numbers are readily understandable by clients to explain severity. We do these measurements for to inform clients and also to allow us to monitor progress over treatment and time.

We continue to move down the leg. If we look at our numbers, we went eight, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20. So we’re measuring every two centimeters here because this is where the severity of the lesion is. The substantial lesion is clearly visible inside that SDFT.

This image reminds us that we should always do a cross sectional and longitudinal exam. It’s really helpful to know how big your probe is. Most probes are around four centimeters. You’re able to put your probe and label it 12 to 16 centimeters distal to the accessory carpal bone, and then if you move down the length of your probe, you know that you’re at 16 to 20 centimeters distal to the accessory carpal bone.

These images above show the difference between the horse’s normal leg on the right and the injured one on the left. We can see here that we’re at the same distance below the accessory carpal bone, 14 centimeters on both images. The damaged SDFT on the left is 1.46 centimeters squared. And then on our right it’s 0.76 centimeters squared. So, we’re approximately double the size there.

When you show this comparison to your clients, with good quality ultrasound images, the pathology becomes really obvious to them, even if they’re not trained in reading ultrasounds. It’s a really nice way to communicate with your clients.“

Dr. Elliott started his career in mixed animal practice on the Mornington Peninsula in Victoria after graduating from the University of Queensland in 2007. He has focused on equine medicine and rehabilitation for the past 12 years in Australia and the United Kingdom. When the pandemic struck, he set up a new race track equine practice in Australia instead. Watch the full one-hour webinar to learn more from Dr. Elliott: 10 Ways Ultrasound Helped My Equine Veterinary Practice.